From 19 September to 13 December 2021, Cumbre Vieja, in La Palma, erupted. Many on the island have observed the lava flows reaching the sea for the first time: before then, in fact, the last volcanic event dated back to 1971.

To find out more, we hosted Luca D'Auria, director of the volcanic surveillance area of the Volcanological Institute of the Canary Islands, INVOLCAN, who in the past also worked at the INGV Vesuvius Observatory in our virtual living room. D'Auria told us some moments of his personal and professional life providing interesting information on the volcanism of the Canary Islands.

Director, when was your passion for science born?

Since I was a child I have had a strong passion for science and, in particular, for the study of the Earth and associated phenomena, such as volcanoes and earthquakes.

Since I was a child I have had a strong passion for science and, in particular, for the study of the Earth and associated phenomena, such as volcanoes and earthquakes.

I was born at the foot of Vesuvius, which I have always considered a member of the family, and I lived through the experience of the tragic earthquake that struck Irpinia in 1980.

It was therefore natural for me, given personal interest and life circumstances, to pursue a career of study focused on volcanic seismology.

What scientific achievement are you most proud of?

Some of the articles of which I am the first author have had many citations but I confess that the publication of which I am most proud is not among them, and it was one of the first.

It was the year 2005 and I was working at the INGV Vesuvius Observatory, when one day a roar was heard by the inhabitants of the island of Ischia; no immediate explanation was found for the phenomenon and what happened remained a mystery for several weeks.

Well, I had the pleasure of discovering that it was the shock wave of a meteorite that exploded in the atmosphere above Ischia. It was a different area from mine; for this reason it was a satisfaction to see my hypothesis confirmed, the same emotion you feel when you win a challenge.

Was there an event that was particularly decisive for you in your professional career?

Yes, the Stromboli emergencies that occurred in 2003 and 2007 were particularly decisive for me, and for the entire Italian volcanological community.

On 5 April 2003, while the volcano continued to emit lava from a vent located at 550 m, a violent paroxysmal explosion occurred at the central craters and some blocks expelled by the volcano fell back to low altitudes on the south-western slope, hitting some houses in the hamlet of Ginostra. In 2007, however, significant changes in the state of the Stromboli volcano were recorded, and a period of effusive activity followed.

The scientific community, initially fragmented into institutes and lines of research, in 2003 came together and "amalgamated" to study the ongoing phenomenon. It was the first emergency I was involved in at work and it proved to be a very stimulating experience, as was the one four years later.

What are the differences between the Italian volcanoes and those of the Canary Islands?

The Italian volcanoes originate from the subduction of the Adriatic plate which is located under the Tyrrhenian Sea and are generally more explosive than those of the Canary Islands. Their characteristics vary according to the position in which they are found: for example Stromboli is very different from Vesuvius, which, in turn, is different from Campi Flegrei.

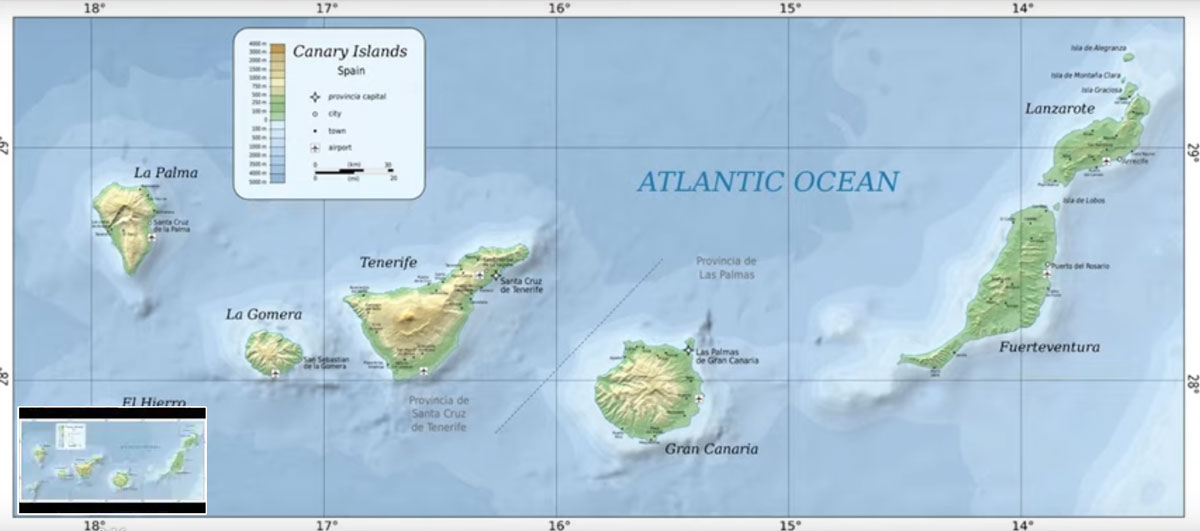

In the Canaries there is a volcanism called hot spot (hot spot) in which the islands are formed, evolve and "die" following a cycle lasting several tens of millions of years, quite well known.

The western islands are the youngest, La Palma is an example; going east, however, they are in an advanced evolutionary stage. Think of Fuerteventura, where there is almost no volcanic activity and the land is almost completely eroded.

Wanting to make a comparison between the volcanoes of the Canary Islands and the Italian ones, the most similar is certainly Etna, even if unlike the latter the former do not have a clearly evident central building, with the exception of Teide.

In La Palma, where the Cumbre Vieja volcano is present, the eruptive centers can open anywhere in the central part of the island. Despite the name, which translated means "Old Mountain", in fact there is no mountain but a set of volcanic fields with many small cones that originate individual eruptions.

This is a common feature of many volcanic islands where there are no obvious buildings such as those on Vesuvius, Stromboli or Etna.

What kind of relationship binds the population of La Palma to the volcanism of the island?

In the mythology of the population present on the island before the Spanish conquest, that of the Guanches, of Berber origin from North Africa, we find several divinities linked to volcanism, which denotes a strong bond in the past that has its roots in prehistory.

Currently the inhabitants of the Canaries are culturally linked to volcanism but, unlike what happens in Italy with Etna and Stromboli, whose activity is visible and persistent, there the active islands have one, maximum two, eruptions every century.

This is why the eruption caught many by surprise: the last eruptive activity of Cumbre Vieja took place in 1971 and, although some of the inhabitants of La Palma remember it, for most of the islanders the recent event was experienced as something again.

I think that the times that have elapsed between the previous eruptions, long in terms of human life, contribute to underestimating the perception of volcanic risk by many.

What kind of volcano is Cumbre Vieja?

In the common imagination a volcano is represented by a truncated external cone but the Cumbre Vieja has a different structure, typical of the hotspots of the oceanic islands.

There is no central building, but an alignment of craters, formed in the last million years, where the so-called monogenic volcanoes are frequent, small cones that form during an eruption and then are no longer activated.

Even in Tenerife, where there is a very evident and famous central building, Teide, which is also the highest volcano in Europe, most of the historical and prehistoric eruptions have occurred relatively far away, in lateral areas similar in characteristics to the eruption recently occurred in La Palma.

What was your experience at INGV?

I started working at INGV immediately after my doctorate, and I immediately found myself grappling with the Stromboli emergency of 2003. For me, INGV was a school, a fundamental training ground for scientific training and for learning management of volcanic emergencies. I worked for the Institute until 2016, but I still collaborate closely with the INGV colleagues, who are also present here in La Palma to study the eruption that began last September, which, from a scientific point of view, proved to be very interesting.

What kind of organization is INVOLCAN?

INVOLCAN is a research institution founded about ten years ago with the aim of grouping the resources on volcanological and geothermal research present in the Canary Islands under one roof. This initiative was launched by the government of the Island of Tenerife which currently holds 100% of the shares of the entity, which, although legally a private company, is in practice public. The intention of the Canarian government is to buy 60% of the shares, to which the contributions of the islands would be added, each with its own government with economic and political powers. I hope that INVOLCAN will become an entity shared by various political and social components and that the various national ministries will also join this initiative to bring together all the human and technological resources available for volcanological and geothermal research in the Canary Islands.

How do you find the Spanish search system compared to the Italian one?

The Spanish research system, like the Italian one, is structured on different levels: national, regional and local. At the national level, however, I find it more flexible. In Italy, tenders and projects are generally quite homogeneous. In Spain, on the other hand, I find that the opportunity is varied; it is possible to participate in specific projects for the acquisition of infrastructures, for cutting-edge research, for tackling applied research problems and for responding to concrete problems of society. Furthermore , many projects are aimed at acquiring national and international human resources .

The Spanish research system, like the Italian one, is structured on different levels: national, regional and local. At the national level, however, I find it more flexible. In Italy, tenders and projects are generally quite homogeneous. In Spain, on the other hand, I find that the opportunity is varied; it is possible to participate in specific projects for the acquisition of infrastructures, for cutting-edge research, for tackling applied research problems and for responding to concrete problems of society. Furthermore , many projects are aimed at acquiring national and international human resources .

At the regional level the projects are more directed towards applied research and locally there are various opportunities, such as the one offered by the government of Tenerife which finances projects related to the various aspects of research.

We receive funding not only for volcanic monitoring but also for the exploration of any geothermal resources, for the study of the quality of the environment with respect to air pollution and aimed at agri-food quality.

In conclusion, what is the volcanological result that you would like the scientific community to achieve as soon as possible?

Surely the goal is to improve prediction of long-term eruptions. On the one hand there is volcanology, which allows us to reconstruct the volcanological history of an island or a region, thus providing statistics on the number of eruptions that have occurred every century. In this way we have the tools to understand if a certain region can be affected by an event and of what type. On the other hand, when the volcano begins to show signs of restlessness, geophysics and geochemistry allow us to understand its state.

The eruption that took place in La Palma has shown that although the precursors were very short, about a week, geophysics made it possible to follow the evolution of the earthquakes and the deformation of the ground in great detail, making it possible to identify, albeit with little warning, where the eruption would have occurred and its characteristics. What is missing at present is being able to understand whether the volcano, even in the absence of macroscopic signals such as earthquakes or ground deformations, is approaching an eruptive phase.

This is still a challenge that requires pure and applied research, as well as the development of technologies, and is of great interest not only for the volcanic areas of the Canary Islands but also for Italian volcanoes such as Vesuvius and Campi Flegrei, where it is necessary to know as early as possible if you are entering an eruptive phase. The ideal would be to have the information a few years earlier, but in the current state of knowledge and technology it is still not possible. I think this is the main goal of modern volcanology, to be able to predict eruptions long before they happen.