Definito il campo magnetico terrestre in Medio Oriente tra 10.000 e 8.000 anni fa. I risultati offrono nuovi elementi per la comprensione del campo magnetico attuale

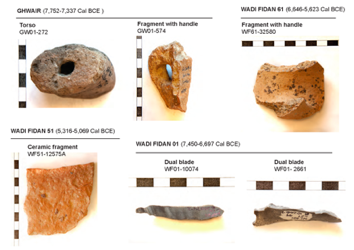

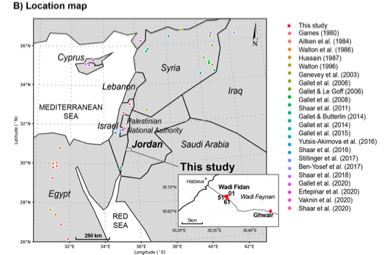

Un team internazionale di ricercatori dell'Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), dell'Università di Tel Aviv (Israele), del Council for British Research in the Levant (CBRL) e dell'Università della California di San Diego (USA) ha analizzato ceramiche e selci provenienti da quattro siti archeologici in Giordania.

Il gruppo di ricerca ha scoperto che tra 10.000 e 8.000 anni fa l’intensità del campo magnetico nella regione del Medio Oriente era tra le più deboli dell’Olocene e più bassa o simile al campo magnetico del presente. Un campo magnetico debole implica un indebolimento dell’effetto di schermatura delle radiazioni solari con una maggiore penetrazione delle particelle energetiche solari e dei raggi cosmici verso la superficie terrestre.

Il nuovo studio approfondisce la nostra conoscenza del campo magnetico nel passato per comprendere il comportamento del campo magnetico attuale, caratterizzato da un marcato indebolimento. I risultati dello studio “The strength of the Earth’s magnetic field from Pre-Pottery to Pottery Neolithic, Jordan” sono stati pubblicati sulla rivista PNAS.

“Il campo magnetico terrestre”, spiega Anita Di Chiara, ricercatrice INGV e coautrice dello studio, “è cambiato in modo significativo in passato. Set di dati accurati del passato forniscono uno strumento in più per comprendere il presente, nonché un valido metodo di datazione che può essere utilizzato in alternativa al metodo del radiocarbonio”.

“Sono state esaminate ceramiche e selci”, prosegue Di Chiara, “datate poi attraverso il metodo del Carbonio 14 (radiocarbonio) e studiate attraverso tecniche di paleointensità volte a definire l'intensità del campo magnetico del passato. Dalla selce, infatti, venivano ricavati oggetti di pietra, come per esempio le punte di freccia o le lame, utili per la caccia. Per far ciò, gli uomini antichi li lavoravano con il fuoco per renderli appuntiti e quando questi materiali si sono raffreddati, i minerali magnetici in essi contenuti si sono orientati con il campo magnetico all'epoca esistente che, in tal modo, si è ‘registrato’ negli utensili analizzati. Noi siamo andati alla ricerca di questa informazione ‘impressa” scoprendo che nel sito più antico, risalente a 10.000 anni fa, il campo magnetico era simile o più’ basso del campo magnetico presente”.

“Questo risultato”, aggiunge la ricercatrice, “è importante perché anche il campo magnetico attuale è quasi il più basso dell’Olocene (epoca geologica corrente). La metodologia di ricerca impiegata fornisce uno strumento di datazione molto potente perché qualunque oggetto di cui non sappiamo l’età archeologica, può essere analizzato con la tecnica del paleomagnetismo e dell'archeo intensità: con la definizione di una curva di variazione di intensità del campo magnetico per le ultime migliaia di anni è possibile ascrivere gli oggetti ad un determinato periodo archeologico. Tale aspetto è particolarmente utile ai ricercatori del clima e dell’ambiente anche perché l'intensità del campo magnetico attuale mostra una tendenza decrescente”.

Lo studio attraverso la tecnica della paleointensità unita all'archeologia si chiama archeomagnetismo.

“La ricerca continua”, conclude Anita Di Chiara. “Raccoglieremo ulteriori dati su questi siti al fine di estendere la curva delle variazioni di intensità del campo terrestre nel passato, anche attraverso l'analisi degli oggetti in pietra, utilizzati da molto prima della ceramica”.

Link:

Reconstructed the magnetic field between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago from prehistoric flints

Defined the Earth's magnetic field in the Middle East between 10,000 and 8,000 Years ago. The results offer new insights into the current magnetic field.

An international team of researchers from the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), Tel Aviv University (Israel), the Council for British Research in the Levant (CBRL) and the University of California San Diego (USA) analyzed pottery and flint from four archaeological sites in Jordan.

The research team found that between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago the magnetic field strength in the Middle East region was among the weakest in the Holocene and lower than or similar to the present magnetic field. A weak magnetic field implies a weakening of the shielding effect of solar radiation with a greater penetration of solar energy particles and cosmic rays towards the Earth's surface.

The new study deepens our knowledge of the magnetic field in the past to understand the behavior of the current magnetic field, characterized by marked weakening. The results of the study "The strength of the Earth's magnetic field from Pre-Pottery to Pottery Neolithic, Jordan" were published in the journal PNAS.

“The Earth's magnetic field”, explains Anita Di Chiara, INGV researcher and co-author of the study, “has changed significantly in the past. Accurate datasets from the past provide a tool to understand the present, as well as a valid dating method that can be used as an alternative to the radiocarbon method”.

"Ceramics and flint were examined", continues Di Chiara, "from archeological sites previously dated through the method of Carbon 14 (radiocarbon). We used paleointensity techniques to define the intensity of the magnetic field of the past. Flint are stone objects, such as arrowheads or blades worked with fire to make them sharp and when these materials cooled down. Through the firing process, the magnetic minerals contained in them oriented themselves with the existing magnetic field which, in this way, was registered in the analyzed tools. We went in search of this "imprinted" information and discovered that in the oldest site, dating back to 10,000 years ago, the magnetic field was similar to or lower than the magnetic field present".

"This result", continues the researcher, "is important because even the current magnetic field is almost the lowest in the Holocene (current geological epoch). The research methodology used provides a powerful dating tool because any object whose archaeological age we do not know can be analyzed with the technique of paleomagnetism and archeointensity: by defining an archaeomagnetic secular variation curve of the magnetic field intensity for the last thousands of years it is possible to ascribe the objects to a specific archaeological period. This aspect is also particularly useful to climate and environmental researchers also because the intensity of the current magnetic field shows a decreasing trend".

The study through the paleointensity technique combined with archeology is called archaeomagnetism.

“The research continues”, concludes the researcher. "We hope to collect further data on these sites in order to extend the curve of variations in the intensity of the terrestrial field in the past, also through the analysis of stone objects, used long before ceramics".

Link: