Individuato il “cuore pulsante” dell’Etna dallo studio delle fontane di lava del 2015

Un sistema di alimentazione con due serbatoi magmatici, posti a differenti profondità, identificato come meccanismo alla base delle fontane di lava che hanno interessato l’Etna nel 2015

[Roma, 21 maggio 2021]

Un funzionamento simile a quello di un cuore pulsante, con un serbatoio magmatico più profondo che ne alimenta costantemente uno più superficiale, dove i gas pressurizzano dando origine alla raffica di fontane di lava: è il risultato del modello elaborato per l’Etna da un team di ricercatori dell’Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), appena pubblicato sulla rivista scientifica ‘Applied Sciences’.

Lo studio, dal titolo “Combining high- and low-rate geodetic data analysis for unveiling rapid magma transfer feeding a sequence of violent summit paroxysms at Etna in late 2015”, si è concentrato su una serie di quattro fontane di lava che hanno interessato il cratere Voragine del vulcano siciliano nel dicembre del 2015.

Gli scienziati hanno analizzato le deformazioni del vulcano per risalire alle sorgenti magmatiche delle sequenze delle violente eruzioni, per comprenderne le dinamiche e definire il sistema di alimentazione dell’Etna in grado di produrre un così rapido accumulo e violento rilascio del magma.

“La nostra analisi dei dati di deformazione del suolo, ottenuti utilizzando dati ad alta frequenza tilt e GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) e immagini satellitari DInSAR (Differential Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar), ha riguardato un periodo di 12 giorni comprendente l’intera sequenza eruttiva del dicembre 2015”, spiega Alessandro Bonforte, ricercatore dell’INGV e primo autore dell’articolo. “Tali misurazioni ci hanno permesso di definire le complesse interazioni tra le diverse zone di stoccaggio in cui è stato temporaneamente immagazzinato il magma eruttato con i parossismi”.

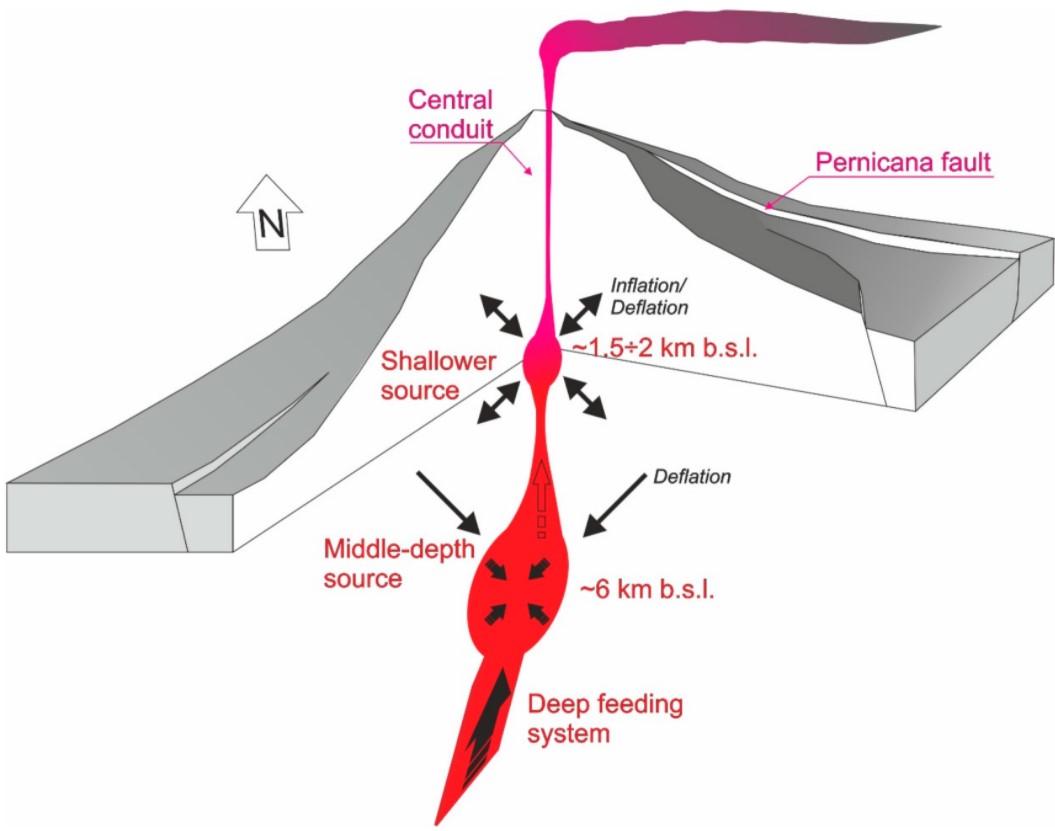

Lo studio ha consentito di definire le dinamiche e le velocità di trasferimento del magma da una camera magmatica profonda a una più superficiale. Lì il magma, ricco di gas, staziona temporaneamente accumulando pressione.

“La sorgente di pressurizzazione profonda fornisce magma ricco di gas a un serbatoio più ‘superficiale’ situato a una profondità di circa 1,5/2 km”, spiega Bonforte. “Quando la pressione del gas supera quella di contenimento delle rocce si verifica l’eruzione violenta sotto forma di parossismo. Questo meccanismo combinato di due livelli di ‘stoccaggio’ del magma a diverse profondità rappresenta, dunque, il possibile ‘motore’ delle sequenze di eventi così rapidi e violenti”.

Tali parossismi drenano non soltanto il materiale magmatico accumulato nel serbatoio più superficiale, ma anche parte di quello che staziona nel resto del sistema di alimentazione del vulcano, con tasso eruttivo di oltre 300 metri cubi al secondo. Viceversa, quando la pressione del gas diminuisce, il parossismo si arresta, diciamo che la valvola si chiude, e il serbatoio più profondo (situato a circa 6 km di profondità) inizia nuovamente a ricaricare quello superficiale, così come il flusso sanguigno nel cuore che viene pompato dall’atrio al ventricolo e poi dal ventricolo all’esterno del cuore.

“Il modello da noi proposto, dunque, suggerisce un meccanismo simile a quello di un cuore pulsante, in cui un serbatoio di media profondità, a circa 6 km, carica un serbatoio più superficiale, a circa 2 km; questo serbatoio si trova ad una profondità che consente al gas di separarsi dal resto del fuso, aumentando così la pressione, un po’ come quando si vedono le bollicine formarsi in una bottiglia di una bevanda gasata. Tutto tace finché la pressione esercitata dal gas presente all’interno del magma non risulta troppo elevata, in sostanza si apre la valvola e si verifica il parossismo, che drena il magma dalla sorgente più superficiale e dal resto del sistema, che è continuo. Una volta scaricata la pressione in eccesso, la valvola si chiude e il ciclo ricomincia, col magma che riprende a spostarsi dal serbatoio profondo a quello superficiale. Questo meccanismo potrebbe rappresentare un modello concettuale valido per eventi di natura simile sull’Etna e su altri vulcani nel mondo”, conclude Bonforte.

Lo studio ““Combining high- and low-rate geodetic data analysis for unveiling rapid magma transfer feeding a sequence of violent summit paroxysms at Etna in late 2015” è stato pubblicato sulla rivista ‘Applied Sciences’ (in calce l’Abstract).

Link all’articolo:

--------

Abstract

We propose a multi-temporal-scale analysis of ground deformation data using both high-rate tilt and GNSS measurements and the DInSAR and daily GNSS solutions in order to investigate a sequence of four paroxysmal episodes of the Voragine crater occurring in December 2015 at Mt. Etna (Italy). The analysis aimed at inferring the magma sources feeding a sequence of very violent eruptions, in order to understand the dynamics and to image the shallow feeding system of the volcano that enabled such a rapid magma accumulation and discharge. The high-rate data allowed us to constrain the sources responsible for the fast and violent dynamics of each paroxysm, while the cumulated deformation measured by DInSAR and daily GNSS solutions, over a period of 12 days encompassing the entire eruptive sequence, also showed the deeper part of the source involved in the considered period, where magma was stored. We defined the dynamics and rates of the magma transfer, with a middle-depth storage of gas-rich magma that charges, more or less continuously, a shallower level where magma stops temporarily, accumulating pressure due to the gas exsolution. This machine-gun-like mechanism could represent a general conceptual model for similar events at Etna and at all volcanoes.

------

PRESS RELEASE

Identified the "beating heart" of Etna from the 2015 lava fountains

A feeding system with two magmatic reservoirs, located at different depths, identified as the mechanism underlying the lava fountain episodes occurred on Etna in 2015

[Rome, May 21, 2021]

An operation similar to a beating heart, with a deeper magma reservoir that constantly feeds a shallower one, where the gas pressurizes, giving rise to the burst of lava fountains: it is the result of the model developed for Etna by a team of researchers of the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), just published in the scientific journal ‘Applied Sciences’.

The study, entitled “Combining high- and low-rate geodetic data analysis for unveiling rapid magma transfer feeding a sequence of violent summit paroxysms at Etna in late 2015”, focused on a series of four lava fountains produced by the Voragine crater of the Sicilian volcano in December 2015.

Scientists analyzed the deformation of the volcano to trace the magmatic sources of the sequence of violent eruptions, in order to understand their dynamics and to define the feeding system of Etna able to produce such a rapid accumulation and violent release of magma.

“Our analysis of the ground deformation data, obtained using high-rate tilt and GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) data and DInSAR (Differential Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar) satellite images, covered a period of 12 days encompassing the entire eruptive sequence in December 2015”, explains Alessandro Bonforte, INGV’s researcher and first author of the article. “These measurements allowed us to define the complex interactions between the different storage volumes where the magma, erupted during the paroxysms, was temporarily stored”.

The study made it possible to define the dynamics and transfer rates of magma from a deep magma storage to a shallower one. There the magma, rich in gas, temporarily settles, building up pressure.

“The deeper storage supplies gas-rich magma to a more ‘superficial’ reservoir located at a depth of about 1.5 / 2 km”, explains Bonforte. “When the gas pressure exceeds a threshold pressure, a violent eruption occurs in the form of paroxysm. This combined mechanism of two levels of ‘storage’ of magma at different depths therefore represents the possible 'engine' of such rapid and violent sequences of events”.

These paroxysms drain not only the magma accumulated in the most superficial reservoir, but also part of the magma stationing in the rest of the volcano’s feeding system, with an eruptive rate of more than 300 cubic meters per second. Conversely, when the gas pressure decreases, the paroxysm stops, let's say that the valve closes, and the deeper reservoir (located about 6 km deep) begins to refill the superficial one again, like the flow in the heart, pumping the blood from the atrium to the ventricle and then from the ventricle to outside the heart.

“The model proposed, therefore, suggests a mechanism similar to that of a beating heart, in which a medium depth storage, at about 6 km, feeds a shallower one, at about 1.5 / 2 km; this shallower reservoir is located at a depth that allows the gas to separate from the rest of the melt, thus increasing the pressure, like when you see bubbles forming in a bottle of a fizzy drink. Everything is quiet until the pressure exerted by the gas inside the magma is too high, essentially the valve opens and paroxysm occurs, draining the magma from the most superficial tank and from the rest of the system, which is continuous. Once the excess pressure has been released, the valve closes and the cycle begins again, with the magma starting again to move from the deep reservoir to the superficial one. This mechanism could represent a valid conceptual model for events of a similar nature on Etna and on other volcanoes in the world”, concludes Bonforte.

The work Combining high- and low-rate geodetic data analysis for unveiling rapid magma transfer feeding a sequence of violent summit paroxysms at Etna in late 2015 has just been published in 'Applied Sciences

Link:

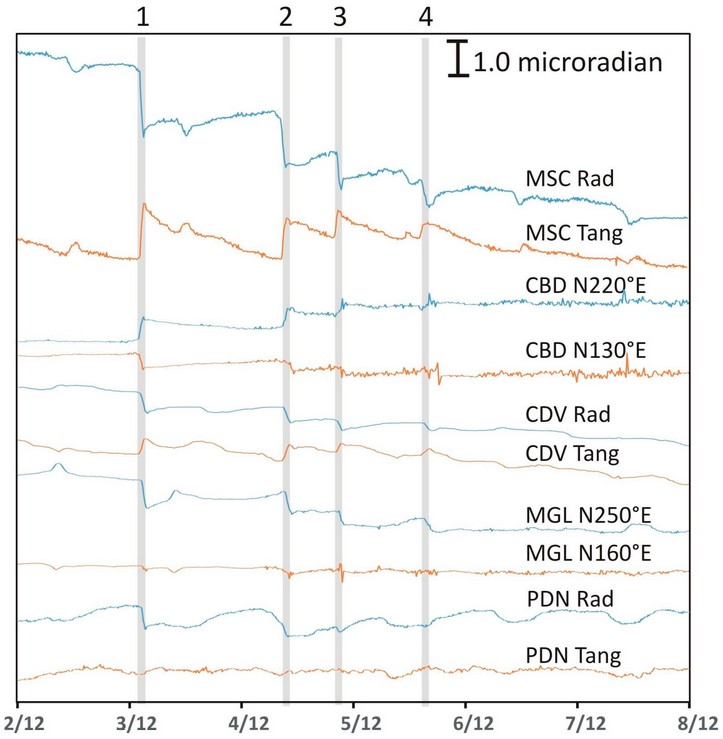

Figura 1 Le variazioni di inclinazione del suolo nei tracciati dei sensori tilt registrano e mostrano chiaramente le pulsazioni della sorgente superficiale con l'impulsivo svuotamento per ciascuna delle 4 fontane di lava e la lenta ricarica negli intervalli

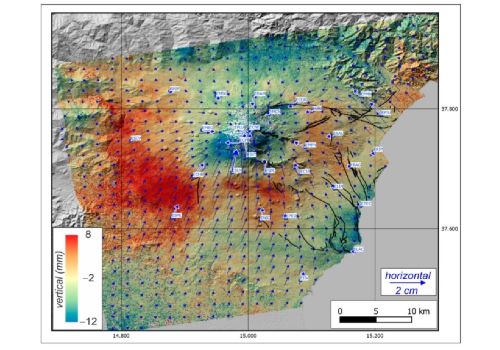

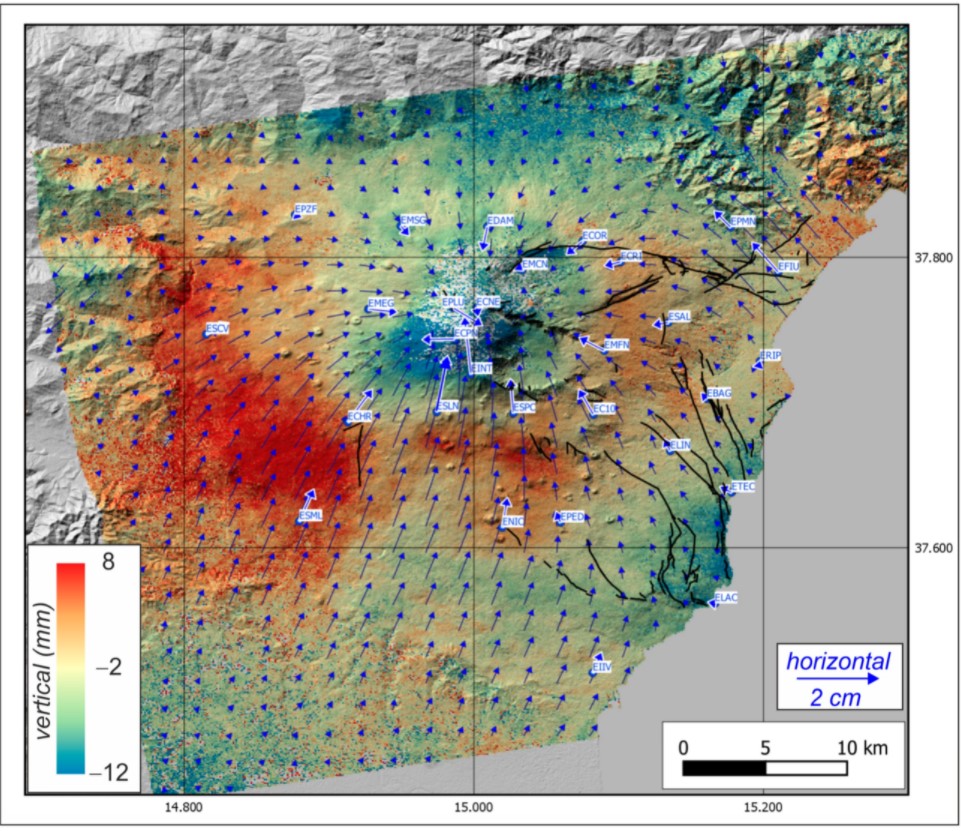

Figura 2 L'integrazione delle diverse misure (GNSS e Radar satellitari) sull'intero periodo di 12 giorni mette in evidenza la rapida contrazione dell'edificio, dovuta allo svuotamento complessivo del sistema di alimentazione più profondo dell'Etna

Figura 3 Schema semplificato del modello finale, con la zona di stoccaggio più profondo (l'atrio), a 6 km, che alimenta quella più superficiale (il ventricolo) dove il magma pressurizza per venire eruttato episodicamente non appena la pressione supera la soglia